An introduction to, and reflections on, three Marlboro legends: Felix Galimir, Alexander Schneider and Pablo Casals

Felix Galimir

One of the most important figures in Marlboro history entered the scene in 1954. Invited by Herman Busch, violinist Felix Galimir had never heard of Marlboro. He arrived at the Brattleboro train station during a snowstorm, where Irene Serkin and a jeep awaited him. Once there, “I got the bug!” said the musician many years later in his heavy Viennese accent. That “bug” stayed with him for the rest of his long life of 89 years.

Felix Galimir brought much that was special to Marlboro, including his great knowledge and deep love of the Second Viennese School of composition. Galimir had grown up in Vienna in the 1920’s and 1930’s, fully immersed in that city’s cultural and musical life. The quartet that he formed with his three sisters was closely associated with such giants as Schoenberg, Berg and Webern, and the Galimirs’ recordings of the Berg Lyric Suite and the Ravel Quartet were made under the direct supervision of the composers, winning the Grand Prix du Disque.

Many musicians in the most prominent chamber groups of this century studied with Felix Galimir, but at Marlboro the opportunity to sit at a music stand next to him (he typically would play second violin), working together on music he knew so intimately, was a remarkable experience. Though he was an extremely demanding colleague, young musicians soon recognized the loving warmth that lay under his sometimes acerbic criticisms.

Violist Samuel Rhodes, a Marlboro senior who was invited by Galimir to be in his quartet and later joined the Juilliard, recalled working with him on the fourth Schoenberg quartet. “The struggles I had, and the hours of practice I put in to be worthy both technically and musically of being in the same group as Felix Galimir, played an integral part in forming me into the musician I am today.” Another senior artist, cellist Marcy Rosen of the Mendelssohn Quartet, spoke for many others when she wrote to him: “You have taught and inspired in me a most passionate love of this music and I am so grateful—and I wish there was a way for me to give you so great a gift!”

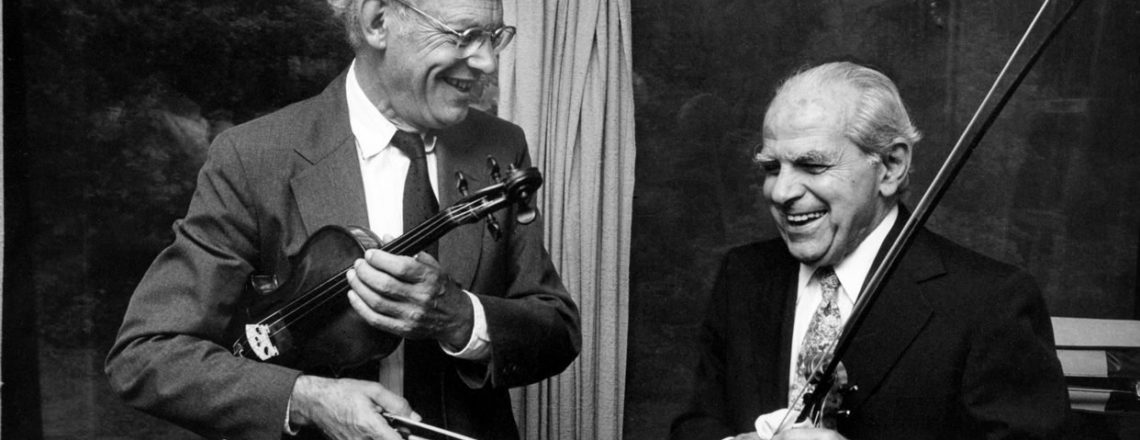

Alexander Schneider

Two years after Galimir’s arrival at Marlboro, a musician of enormous energy and influence entered the scene, remaining for over 20 years. He was Alexander (“Sasha”) Schneider, second violinist of the famed Budapest String Quartet and also a conductor. The Russian-born musician also helped Pablo Casals found the Prades Festival and the Casals Festival in Puerto Rico.

Schneider has been described as a “spitfire,” a “revolution,” a “mover and shaker” whose love of life enveloped everyone in his presence. “I never saw anybody with so much fire in him as Sasha,” said pianist Luis Batlle. At Marlboro, Schneider guided innumerable groups, encouraging players—and yelling in his heavy Russian accent when he didn’t approve. He was a major influence on such ensembles as the Guarneri Quartet, during its founding at Marlboro.

The Guarneri’s violist, Michael Tree, remembers that “Sasha would usually play second violin, where he could really keep tabs on everything and everyone around him. He was able to express every bit of himself through his playing, which sounds easy, but many people are somehow blocked and don’t have that easy access. But he really spoke to you. The moment he started playing you knew you were in his presence.” The word “espressivo,” which has often been used to describe the characteristic Marlboro sound, especially in the strings, is closely linked with Schneider.

Pablo Casals

In 1960, thanks to the efforts of Sasha Schneider, Pablo Casals, who at the time was living in Puerto Rico, was persuaded to come for the first of his remarkable thirteen summers at Marlboro. Schneider had the strong support of Rudolf Serkin, who felt that the Spanish musician had unique musical ideas to share with all participants, by means of his master classes and orchestra readings.

Typically wrapped in coat, scarf and gloves, with a cap over his bald head and the windows closed no matter what the temperature, Casals would be helped onto the podium. Once there, he was transformed by the music into a young man.

Under Casals, said composer Leon Kirchner, “Marlboro was without question, one of the greatest orchestras in the world” Casals approached the symphonic repertoire as if it were chamber music, with every voice of crucial importance. He would have the ensemble play short phrases over and over, to the point of exhaustion. Obsessed with the “long line” and with communicating the very essence of a work, he could not bear to hear a phrase repeated in the same way (“Every leaf of a tree is different,” was one of his favorite lines.) His sense of form, proportion, detail, timing, were extraordinary.

New York Times critic Peter Heyworth attended a 1966 performance of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony with Casals at the podium, writing: “How can I communicate the rough-hewn directness of that sublime performance? It was, as another audience member later said, ‘a roaring lion.'”