The great cellist, conductor, and composer Pablo Casals first came to Marlboro in 1960. Widely considered the foremost cellist of the 20th century, he had fled Franco’s Spain for Prades, in the Pyrenees of southern France, and vowed not to play or conduct in any country that recognized Franco’s Fascist regime.

The violinist Alexander Schneider, who felt that Casals had a great gift that should be shared, brought a group of distinguished musicians to him in 1950 in order to found the Prades Festival. Rudolf Serkin was among the artists who came to Prades, and his great admiration for Casals as well as his close bond with Alexander Schneider led to the invitation for Casals to come to Marlboro in 1960 for two weeks.

Serkin felt that Casals had something musically unique to offer Marlboro’s exceptional young musicians and the entire Marlboro Music community. The participants that summer included pianists John Browning, Richard Goode, Anton Kuerti, and Peter Serkin; string players who would go on to form or join the Guarneri and Juilliard String Quartets; others, including woodwinds, who would become principals and members of the Boston, National, and Toronto Symphonies and Cleveland and Minnesota Orchestras; and singers who would go on to perform with the Metropolitan Opera as soloists with orchestras around the country. They were all to benefit from the insights of Maestro Casals—both from his cello master classes and from the orchestral performances that he conducted, including Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, Mozart’s Symphony No. 29 in A Major, K. 201, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in B-flat Major, Op. 60.

Even though the New York Times ran an article on Marlboro in 1956, the Festival at that time was still known only to a relatively small circle of musicians, some music-loving Vermont neighbors, and northeast fans of Rudolf Serkin. Pablo Casals changed all that. His only recent performance in the U.S. had been at the United Nations, and the rare opportunity to see him in the neutral setting of Marlboro, at a retreat for young musicians, attracted swarms of visitors and abundant international attention. Sometimes these newcomers were rewarded with one of his performances, but they also learned something else: that anything performed at Marlboro was likely to be exceptional.

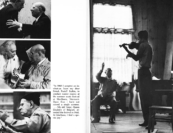

Pablo Casals coaches Michael Grebanier in a master class (photo by Clemens Kalischer); the Casals’s summer home; visiting Vice Presdent Hubert Humphrey, a friend of Rudolf Serkin from his days as Mayor of Minneapolis, greets the Maestro after a concert (photo by John Snyder).

For the 84-year-old Maestro, Marlboro proved an equal revelation. He was impressed by Marlboro’s deep devotion to the exploration of music and by the importance of passing on insights to extremely gifted and enthusiastic young musicians. Casals described Marlboro as a unique institution: “a temple of music.” It drew him back to Vermont for even longer visits over the course of 12 more summers, the last of which took place just a few months before his death in 1973, at almost 97 years old.

Casals left a remarkable legacy at Marlboro in rehearsals, concerts, and recordings of orchestral works by Bach (the Brandenburg Concertos and Orchestral Suites), Haydn, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert, and Schumann. An orchestral focus was new to Marlboro, but in this case rather fitting, for Casals approached the symphonic repertoire as if it were chamber music. Invariably, he approached each work as if it were newly composed and infused it with his own rigorous standards of musicianship and expression.

Living in a renovated farmhouse each summer, Casals and his wife Marta became an integral part of our community, enjoying the young participants, older colleagues, and the bracing Vermont air. Graciously receiving visitors from royalty to resident canines, he dressed warmly regardless of the weather, pipe in hand, his smile revealing a clear sense of contentment.

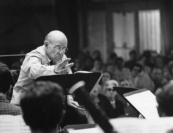

I recall going to his house in Marlboro with Tony Checchia to ask what work he would like to schedule the following week. He was seated in the living room in a large overstuffed chair, seemingly a small, frail figure of limited strength. Tony put the score of a Haydn symphony in his lap, and, as he turned the pages, there seemed to be a magical transformation. His body seemed to expand, his eyes shone, and as he came to the second movement, he said with great emotion, “Ah, when I conducted this work in Barcelona in 1897, the oboe player phrased the opening soooo beautifully.” We experienced similar revelations at his concerts. Slowly and carefully, he was helped to the podium by two musicians, but once he brought down his baton, he became a dynamic figure. He seemed to be in another world, inside the music, having shed at least 20 or 30 years. The musical results were extraordinary.

His masterclasses were also unforgettable. Not only did Casals offer technical and musical wisdom, when he demonstrated a point on his cello, he drew a sound from his instrument that amazed us all in its volume and quality, often dwarfing the sound of the young cellists who were playing for him. Rudolf Serkin, who had an uncanny sense of what was important for Marlboro and our young players, proved to be right once again.

As Casals’s fellow cellist, David Soyer, once said, “When you heard him play, he gave one the feeling that music was the most important thing at that time. There wasn’t anything else, that was it. That was an incredible gift–a gift to his listeners, and a gift to his students, and a gift to the public.” We all gained enormously from Pablo Casals’s 13 summers at Marlboro.

Filmed in celebration of Casal’s 91st birthday, this Bell Telephone Hour special on Casals at Marlboro features illuminating comments from Rudolf Serkin and Maestro Casals as well as a glimpse into Marlboro rehearsals at a time when icons such as Alexander Schneider, Felix Galimir, and Leon Kirchner were participants.

.

☙ Use the links below to access additional biographical and archival materials. ❧

We recommend refreshing the page if you have any difficulty reading the interactive timeline.